New England Style Architecture

“Name That House!” was originally published in Yankee Magazine

“Name That House!” was originally published in Yankee Magazine

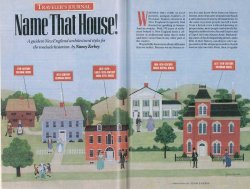

Whether they come as leaf peepers, antiques hunters, or Freedom Trailers, travelers in New England frequently find themselves gawking at houses. And no wonder. With 370 years of settlement behind it, New England hosts a collection of architectural styles that is older and more varied than in any other part of the country.

We probably know more about old houses than we realize. Because we see houses every day and know them from our history lessons, most of us carry around in our heads a subconscious inventory of house forms. In the same way most people can tell a duck from a heron even without knowing its proper name, most people instinctively distinguish a saltbox from a Second Empire and a Cape Cod from a Queen Anne. But knowing some of the distinguishing details, and a little of their history, can deepen one’s appreciation of the unique personality of each town or city one visits. Here, then, is a guide to five common New England house styles dating from 1630 to 1900.

17TH-CENTURY COLONIAL HOUSES (1630-1700, locally to 1740)

Aimee Seavey

Colonial houses are usually side-gabled (roof ends at the sides of the house), flat-faced, wooden structures, covered with narrow pine clapboards, although most of the earliest ones had shingles. With no eaves, shutters, stoops, porches, window trim, or door decoration, these houses present a very plain facade, relieved only in some examples by a jutting overhang of the second story – the “garrison” style. Old and heavy, they seem to grow straight out of the ground.

Colonial houses are usually side-gabled (roof ends at the sides of the house), flat-faced, wooden structures, covered with narrow pine clapboards, although most of the earliest ones had shingles. With no eaves, shutters, stoops, porches, window trim, or door decoration, these houses present a very plain facade, relieved only in some examples by a jutting overhang of the second story – the “garrison” style. Old and heavy, they seem to grow straight out of the ground.

As honest and sturdy as the settlers who built them, these houses were built to take weather. Whenever possible, they were built facing south for winter warmth. Their very steep roofs were designed to shed snow. Small, diamond-paned windows and heavy, vertically planked doors helped keep heat indoors. The massive chimney was usually placed in the center of the roof, but appears as an exterior feature in Rhode Island “stone-enders.”

The original form of Colonial houses was a simple one-room, two-story box. In time, many of the houses were built out backward to make room for growing families and storage goods. The resulting slant-roofed “saltbox” shape was a sure sign that the colonists’ tenuous hold on New England was becoming more secure.

A variation on the theme is the classic Cape Cod house — wood frame, 1-1/2 stories high with a pitched roof, little or no space between windows and roof gutter, and no overhang on the gables. The classic is the full Cape, with a central door, and two windows symmetrically on each side. The three-quarters Cape has two windows on one side of the door and only one on the other side; the half Cape has only two windows and a door to their side.

A variation on the theme is the classic Cape Cod house — wood frame, 1-1/2 stories high with a pitched roof, little or no space between windows and roof gutter, and no overhang on the gables. The classic is the full Cape, with a central door, and two windows symmetrically on each side. The three-quarters Cape has two windows on one side of the door and only one on the other side; the half Cape has only two windows and a door to their side.

GEORGIAN HOUSES (1700-1780, locally to 1830)

In roof form, chimney placement, and cladding, Georgian houses are much like their Colonial predecessors. However, they are bigger, typically two stories high and two rooms deep, and the roofs only moderately pitched. Many were unpainted and often shingled, but some scholars believe they were originally painted in blue-green, salmon, and mustard-yellow colors. What chiefly distinguishes Georgians from Colonials is their civility. As the colonists prospered, their houses became better mannered.

Georgian houses are best identified by the orderly plan of their windows and doors. The window placement on the front facade is absolutely regular. The windows march across the second story, usually at even-spaced intervals and almost always in odd numbers of three, five, or seven across. The lower-story windows appear directly below the uppers with the doorway in the center, making the facade exactly symmetrical. The windows themselves are double-hung, typically with nine to 12 panes per sash.

The windows themselves are double-hung, typically with nine to 12 panes per sash.

Decoration is restrained and focuses on the doorway. The door itself, sometimes a double door, is no longer planked but paneled. Flattened columns flank the door and support an overhead crown, which is most commonly straight or triangular, but is sometimes curved or scrolled. In the high Georgian style, a row of square-toothed dentil molding typically parades along the cornice under the overhanging roof eave.

Georgian houses are like British regimental officers. They are solid, unblinking, upright, and true – and little prone to imagination. They occasionally appear in fancy dress, wearing roof balustrades or pedimented dormers, for instance, but they are essentially soldiers, stoutly defending the good citizens living within their orderly walls.

ADAM-STYLE HOUSES, ALSO CALLED FEDERAL (1780-1820, locally to 1840)

If Georgian houses are soldiers, Federal houses are burghers and princes. The two styles are closely related, but Federal houses can usually be distinguished by their freer, more elaborate detailing. For quick identification, look at the arrangement of glass below the crown of the front doorway: if there is a row of small rectangular windows, the house is almost certainly Georgian; if there’s an elliptical or semicircular fanlight, it’s probably Federal.

On closer inspection, the entire facade is more “glassy.” Vertical sidelights often flank the entrance, making the doorway larger. To balance it, a large, tripartite Venetian or Palladian window sometimes appears above the door on the second story. The panes in all windows are now bigger, sometimes as large as a foot across, and often number six per sash instead of the usual nine or 12 in Georgian’ houses.