Residential Architects Cambridge

Author:

Author:

Publishers:

Cambridge Historical SocietyBY BAINBRIDGE BUNTING

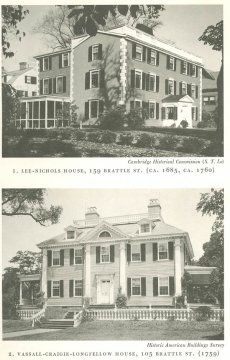

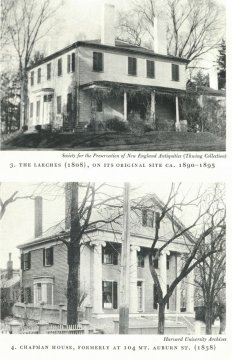

AS implied by the title, the idea underlying this talk is that history is an ongoing process. History is as recent as yesterday, with 1973 or 1873 as much a part of history as 1773— and as important. In terms of architectural history, good buildings of intermediate or recent date are as "historical" and as worthy of admiration and preservation as those erected two hundred years earlier. If specimens of later date are not preserved, through prejudice or neglect, important gaps are created in the long-term record to the detriment of later generations. This is the conviction that underlies the work done by the Cambridge Historical Commission during the decade since it was founded in 1964. And it is because Brattle Street in a remarkable way, perhaps to a degree unequaled anywhere in the United States, preserves specimens of almost every phase of American architectural taste that the Cambridge Historical Commission will propose that street as an historic district.

Before I turn to that area and its houses, however, I cannot resist the opportunity to scold Cambridge history buffs just a little about the arbitrary limits they have sometimes placed on "history." And where could I find a more august, attentive, and captive audience to scold than the one I am honored to address? I have been a Cam-

33

bridge-watcher for the last thirty-five years, a process that began when I came here as a graduate student. Being a Cambridge-watcher, of course, does not qualify me as a Cantabrigian. Indeed, I am very much an outsider, having long ago lost my heart to the Great American Desert. Nevertheless, I have kept in touch with the Cambridge scene by almost yearly visits. It is just possible that this kind of association, detached yet enough in contact, may have provided a certain perspective on Cambridge ways and attitudes. If this is so, then I confess that I have often been amazed and not infrequently amused at the sense of history evinced by some Cambridge citizens. For them, if an event did not happen during or before the Revolution, it is not really historical; if George Washington didn't sleep in the house, it is not historic; if a building is not eighteenth-century, it is not genuinely old and probably not worth preserving. Oversimplified, perhaps, but not entirely without foundation. My awareness of this point of view has been heightened by its sharp contrast with prevailing attitudes in the Rio Grande valley which is now my home. The latter area is both much older and much younger than Cambridge. As for antiquity, men have been building permanent communities there for at least seven hundred years, and even the Spanish newcomers designated Santa Fe as capital of the Provincia de Nuevo Mexico a good twenty years before Newtowne—now called Cambridge—was chosen as the seat of government for the Massachusetts Bay Colony—a fact I cannot resist dragging into a lecture before the Cambridge Historical Society! On the other hand, rates of change in the two areas have been vastly different. Despite an early start, few things changed in the Rio Grande area until the arrival of the railroad about 1880—an undertaking, incidentally, largely financed with Boston money—and drastic change has occurred there only since the Second World War. In addition, very little of the early construction survives because it was built of mud, with the result that what seems venerable in the way of buildings to New Mexicans might appear as merely Victorian to you in New England.

The latter area is both much older and much younger than Cambridge. As for antiquity, men have been building permanent communities there for at least seven hundred years, and even the Spanish newcomers designated Santa Fe as capital of the Provincia de Nuevo Mexico a good twenty years before Newtowne—now called Cambridge—was chosen as the seat of government for the Massachusetts Bay Colony—a fact I cannot resist dragging into a lecture before the Cambridge Historical Society! On the other hand, rates of change in the two areas have been vastly different. Despite an early start, few things changed in the Rio Grande area until the arrival of the railroad about 1880—an undertaking, incidentally, largely financed with Boston money—and drastic change has occurred there only since the Second World War. In addition, very little of the early construction survives because it was built of mud, with the result that what seems venerable in the way of buildings to New Mexicans might appear as merely Victorian to you in New England.