Park Hill Flats

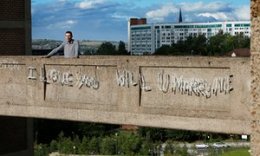

A bridge too far: Jason, next to the neon version of his original message. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Observer

A bridge too far: Jason, next to the neon version of his original message. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Observer

One spring day in 2001 a tall man walked into Sheffield’s Park Hill flats and along a street in the sky. He strode past the brutalist flanks, out on to the footbridge. He thought: this’ll do.

Jason didn’t look down; he gets vertigo and he was 13 storeys up. He leaned over in his yellow Puffa jacket and sprayed her name. “Clare” came out haphazardly and “Middleton” hit the ledge. He planned to take her to the Roxy on the facing hill, to show her. So now he began again, bigger, clearer: “I LOVE YOU WILL U MARRY ME”. It was his two-fingers-up at the social services office opposite. He scarpered. Seeing it, Grenville, one of the estate’s caretakers, said to the on-site office: “How are we going to get that off?”

They didn’t. The graffiti stayed, high above the city, while the city argued about what to do with the flats. Park Hill, the concrete estate behind the railway station, had become notorious. The city projected abandonment on to Park Hill, so the graffiti started to look like love yelling at the top of its voice in an estate thought to be desolate.

Soon it was also looking like PR. In 2006 Sheffield City Council appointed regeneration specialists Urban Splash to redevelop Park Hill. From the start, the company used the graffiti as a slogan to woo Sheffielders back to the epic, undemolishable council blocks of 995 flats, Europe’s largest two-star listed building. “I love you will u marry me, ” sang the flats. Clare was edited out.

“She had difficulty expressing love’: Clare Middleton as a young woman.

“She had difficulty expressing love’: Clare Middleton as a young woman.

Jason didn’t know his proposal had become something else. He didn’t know that Professor Jeremy Till, then at the University of Sheffield, jauntily displayed a replica of the bridge at the 2006 Venice Biennale of Architecture. Or that Urban Splash had replicated the proposal on T-shirts for their launch party and one of the Arctic Monkeys wore one on stage in America.

One day in 2010, I looked up and wondered who the lovers were and whether Clare said yes. I asked film-maker Penny Woolcock to work with me on a documentary for Radio 4, a quest to find the real lovers behind the graffiti. We knew nothing. I rhapsodised to the local paper, The Star, hoping that we would uncover a romance. I trawled local news archives and we chased up rumours. There was one story that Clare Middleton said no to the proposal, so her spurned lover had jumped off the bridge. The Park Hill caretaker, Grenville Squires, said not: 26 other people did jump off the bridge, one of whom Grenville heard yell “help” just before he jumped. But not the graffiti man.

A fork-lift driver had heard it was a love triangle and the person who wrote it had his flat burned out by the other bloke. Grenville said no. He did remember “one or two house burnings on Park Hill but most of them’s been by accident”. He told Penny that brides rode down to their weddings in the estate’s service lifts so that their big frocks didn’t squash. But none of the brides who descended that way was Clare.

A fork-lift driver had heard it was a love triangle and the person who wrote it had his flat burned out by the other bloke. Grenville said no. He did remember “one or two house burnings on Park Hill but most of them’s been by accident”. He told Penny that brides rode down to their weddings in the estate’s service lifts so that their big frocks didn’t squash. But none of the brides who descended that way was Clare.

An artist called Emilie Taylor used to watch drug users snake under the graffiti when she worked on the Needle Exchange van that parked under the bridge. She asked around, because it seemed an intoxicated act, that proposal. But – nothing.

Without answers, I recorded texture. On the bridge I recorded wind, trams, sirens: “There’s always a siren, ” Jason said when we finally met him. I recorded children in the playground of the nursery on Park Hill. It turned out to be the nursery where Clare Middleton played as a child.

That Easter, 2011, I got an email from Tim Middleton: “Regarding your article in the Sheffield Star… Clare Middleton was my step-daughter.”

That Easter, 2011, I got an email from Tim Middleton: “Regarding your article in the Sheffield Star… Clare Middleton was my step-daughter.”

Tim has Love and Hate tattooed on to his knuckles. He was a Hell’s Angel when he married Janet. She had a toddler called Clare. They moved on to Park Hill. Tim, now single, keeps a very clean house on a red-brick estate and his front garden is full of blooming white pot plants. His ex-wife Janet joined us there, and they talked about Clare, dark-skinned and skinny, doing cross-stitch, reading Catherine Cookson, being happy, going clubbing.

Tim thought the graffiti was a nonsense: “Graffiti on a listed building!” They weren’t in touch with the man who’d written the proposal. Janet said: “She was going to marry him but circumstances…” She asked me to turn off the recorder. There were so many things we couldn’t say.

We met Jackie, Clare’s half-sister, in what she calls her “bubble” on another hill in the city. She says Clare loved the proposal, “Best thing anyone’s ever done for her.” Clare was living alone with her two boys, a toddler and a baby, when she met Jason. Penny asked, “Did you love Clare?” Jackie said yes. “I did love her. I didn’t like a lot of what she did.”

When she was young Clare craved love, Jackie said. She devoured Mills & Boon. “She used sex and love as a crutch to prove that her life meant something.” She would go dancing in thigh-length boots and hot pants. She attracted “bad boys”. Jackie described Clare’s life as “a spiral” – spiralling, like she danced.